MARKED MEN

By Conrad Weems

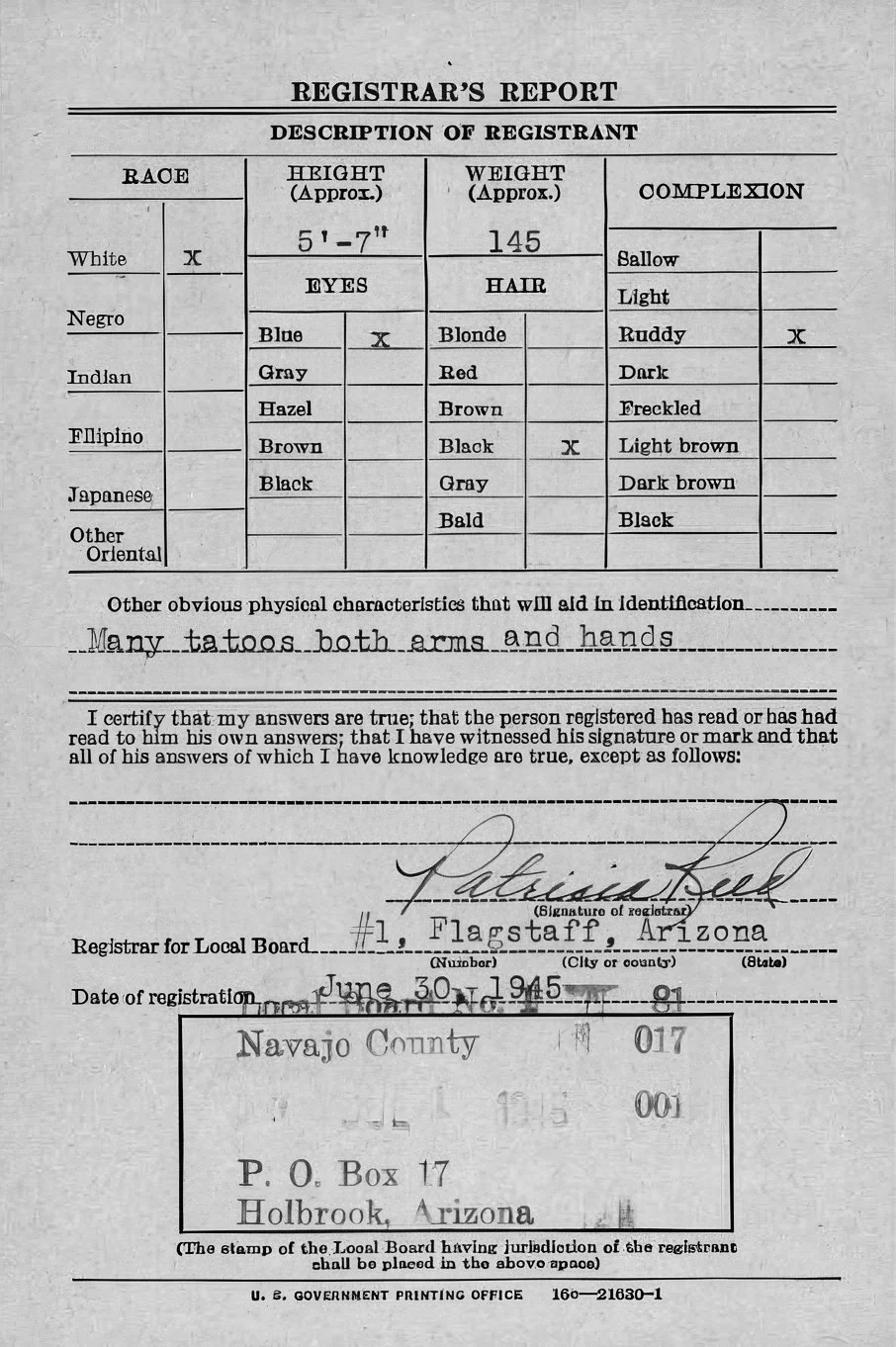

“Many Tattoos both arms and hands”

There’s a space on the back of DSS Form 1 (Rev. 11-16-42), colloquially known as a draft card, labeled ‘Other obvious physical characteristics that will aid in identification.’ It was June 30, 1945, and a registrar named Patricia Reed used what appears to be a Royal KMM Typewriter to make a telling entry regarding my grandfather.

Among those tattoos was his name. “Lloyd” across one hand, “Weems” across the other.

Later in life, during the Korean War, my grandfather served in the Navy, leading me to believe that was where he picked up his many tattoos. His arms bore all manner of art, including at least one scantily dressed lady, and his chest sported a giant bald eagle with ‘US NAVY’ emblazoned beneath it. But as the latest of the Weems family chroniclers, I stumbled upon his 1945 draft card, and that crucial detail from Patricia, which told a different story.

In 1945, a man with tattoos on his hands sent a clear and unmistakable message. In an era when visible ink remained outside the bounds of polite society, such markings weren’t fashionable statements or curated aesthetic choices. They were stark declarations worn by those who either couldn’t (or refused to) conform.

Across the United States in the 1940s, tattoos were primarily the domain of sailors, convicts, carnival workers, and the laboring class. Even within these groups, unspoken but rigid rules prevailed. A forearm tattoo could be concealed by a rolled-down shirt sleeve. A chest piece remained a private matter. But hands? Hand tattoos were bold. They were irreversible. To ink one’s hands in 1945 was to deliberately step beyond the cultural margins of the era.

In the industrial hubs of the East Coast, tattoo parlors clustered near naval ports and red-light districts. Illustrious names like Charlie Wagner and Amund Dietzel crafted bold, utilitarian flash art: anchors, hearts, banners, eagles, and pinups, typically rendered in black and red. These establishments were not artistic sanctuaries; they were veritable factories of instant identity, often little more than storefronts illuminated by flickering neon signs and adorned with flash sheets tacked to the walls.

Fig. 1 - Draft card entry, June 30, 1945The Southwestern Edge // Ink in the Desert

Yet, in the American Southwest (in places like Winslow, Arizona, or Cloudcroft, New Mexico), tattoo culture was even more marginal and far more informal. Winslow, where the Santa Fe Railroad traversed east to west alongside Route 66, was a town in perpetual motion. It was a crossroads for Navajo and Hopi men working seasonal jobs, Anglo families pursuing sawmill contracts, servicemen in transit, and numerous young men drifting toward or away from enlistment. There, a tattoo artist might operate from a back room behind a saloon or a makeshift space within a barbershop. Sometimes, a professional tattooer wasn’t to be found at all; only a friend with a needle, some India ink, and the audacity to try.

It was in such an informal environment that Lloyd, my grandfather, likely acquired his first tattoos. Records indicate that by 1945, despite being only sixteen, he was living in Winslow and already bore ink on his hands and arms. His draft card filed that June listed him as eighteen, a standard wartime fabrication. But the ink was unequivocally genuine. Even before he possessed the proper documentation, he had etched something permanent onto himself.

For men like Lloyd, tattoos transcended mere body art; they were a form of authorship. A name emblazoned across the knuckles wasn’t decorative: it was a claim, a statement of ownership. Some wore them for love, some for remembrance, and some for menace. “That way, if I punched someone, they’d know who did it,” was my grandfather’s response when my brother asked about his name spelled across his hands. While such a remark might sound flippant today, in 1945, it was a profound declaration.

In these remote, working-class towns, there was no gallery, no publisher, and no audience for self-expression beyond the men one toiled beside or shared drinks with. There were sawmills and rail yards, wives and lodgers, dust and sweat. But no platforms. No showcases. To tattoo oneself was to communicate in the only medium that traveled with the body. One wasn’t cultivating a brand; one was staking a claim to a self.

And society took notice. Employers, landlords, and law enforcement invariably interpreted tattoos as markers of deviance, particularly those on the hands. That ink was impossible to hide, impossible to retract. This very permanence was the essence of the statement. In a life of constant flux, tattooing offered stillness; a way to assert, “I was here. I am this.”

Today, tattoos are ubiquitous, having been aestheticized, spiritualized, and monetized. But in 1945, in a dusty town at the desert’s edge, for a boy striving to embody manhood, they were something else entirely. They were a declaration. An act of defiance. Perhaps even the very first artwork he ever created.