Kinko’s saints and the dirt mall gospel

BY THE MOOSE

“We work in the dark—we do what we can—we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”

-HENRY JAMES

“At night, when the objective world has slunk back into its cavern and left dreamers to their own, there come inspirations and capabilities impossible at any less magical and quiet hour. No one knows whether or not he is a writer unless he has tried writing at night.”

-HOWARD PHILLIPS LOVECRAFT

What Got Lost

Before content, there were copies. Before creators, there were kids with glue sticks and dream rot in their teeth.

You’d see them in the fluorescent tomb of a 24-hour Kinko’s — eyes ringed in toner smudge, limbs fueled by diner coffee and stolen cable shows. Making something from nothing. Four bucks to their name, twenty-five pages to go. They weren’t chasing clicks or juicing metrics. They were elbow-deep in glue stick guts, dragging art across the threshold like a body — raw, heavy, and real.

The scene didn’t have a name, not really. Zine culture. Tape swap culture. Mail-art. It was less a movement than a thousand small eruptions — scattered storefronts, rec rooms, trenchcoat distro gods with beat-up Doc Martens and manila folders full of strange gospel. From the late ‘80s through the mid-2000s, there was an entire shadow infrastructure devoted to getting unpolished, unlicensed, unasked-for media into the hands of anyone who might care.

The barriers between artist and audience? Physical. Immediate. And weirdly intimate. You had to put it there — in the laundromat basket, the punk flea table, the crack in a payphone booth. You had to hustle for every set of eyes.

This wasn’t nostalgia — not yet. It was necessity. And it came with a smell: overheated plastic, sweat-soaked paper, Sharpie on fresh sticker stock.

What got lost? The edges. The dirt. The quiet ecstasy of pulling a freshly stapled zine from your backpack and knowing it didn’t exist ten minutes ago.

What got lost? Maybe you, reader. Maybe this was supposed to find you back then — in the corner of a record shop, or tucked inside a bathroom stall door at a basement show. Maybe the signal got scrambled. Maybe this is its return.

Welcome back.

“— scattered storefronts, rec rooms, trenchcoat distro gods with beat-up Doc Martens and manila folders full of strange gospel.”

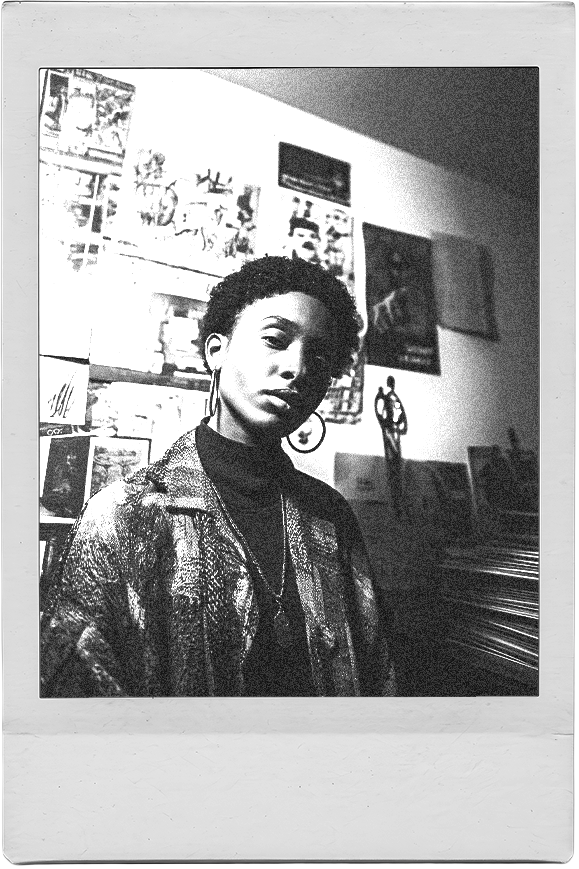

Fig. 1 - Saint Joe of the Stuck TrayFig. 2 - Saint Dominique the GluerThe Gospel According to Kinko’s

The copier was an accomplice. You fed it stolen fire — and it spat back revelation, one grainy page at a time.

Walk into any Kinko’s between midnight and 5AM during the scene’s heyday and you’d find a makeshift congregation. Not the laptop set — this was before Adobe made everyone a designer. These were rogue editors armed with X-Acto blades and glue sticks, junk-shop clip art, stick-on lettering from craft stores, the occasional smear of blood or lip gloss. This was publishing with your whole body.

The machines were moody and loud, whirring like factory ghosts, prone to jamming if the paper was too thick or the collate stack ran too long. But when they ran right, they sang. And in those fluorescent sanctuaries — Kinko’s, OfficeMax, some off-brand shop run by a dude named Jerry who didn’t ask questions — insurgent presses were born. Not with ISBNs or barcodes, but with a bootleg cassette, a staple gun, and a bag of rubber bands.

This was the DIY media production line:

Zines with names like Sad Girl Static, Cursed Transit, How to Hex a Cop.

Hand-dubbed mixtapes with tracklists scrawled on peeling Lisa Frank notebook paper.

Flyers layered like bark on light poles, wheatpasted on overpasses, handed out at 4H fairs and hardcore shows in VFW basements.

Pamphlets on queer ecology, antifascist juicing, or how to fake a nosebleed to get out of class.

Each creator had their style. The zinesters were obsessive — crosshatchers and re-typists, hunting for the perfect Xerox saturation. The riot grrrls brought iconography: safety pins, lipstick fonts, screams in Helvetica. The anarcho-punks went raw and chaotic — glue-caked, barely legible, pure intent. The stoner cartoonists? Surreal as hell. Melting faces, sentient burritos, hand-drawn comics about municipal plumbing conspiracies. And then there were the quiet ones — the outsider essayists — who made five copies of a personal epic about loneliness and left them in diners across the county. Hoping someone would care enough to read.

It wasn’t mass production. It was mass intimacy. You didn’t give a shit about reach. You wanted someone to feel it — like a punch, like a prayer, like the voice in your ribs that says you’re not alone.

And the copy shop? That was your forge. That was your church. That was your motherfucking press.

Fig. 3 - Saint Gail of the Burn PileFig. 4 - Saint Mi-Young of the Double LifeIf Kinko’s was the forge, the field was weirder. Wider. A stitched-together web of vending machines, glove compartments, sticker-coated lockers, and cigarette-burned coffee tables in shared rental basements. No barcode. No shipping logistics. Just the pulpy alchemy of getting your thing into someone else’s hands without the grid knowing.

Start with the dirt mall.

Not the shiny suburban fortress malls — the other ones. The half-abandoned plazas out by the train yards, where only two storefronts still had power: a Family Dollar and a vaguely-legal vape kiosk. There, in an unmarked unit next to a shuttered H&R Block, was a monthly flea that sold nothing new. Bootleg Nirvana shirts, plastic crates of punk 7”s, off-label incense. But in the corner, taped to a folding table with a brick as a paperweight, was a zine pile. Always slightly damp. Always full of miracles.

Out in Providence, there was the backroom at Atlantis Used Records — past the milk crates, past the jazz section, a wall-mounted metal file cabinet labeled “READ ME.” You opened it like a mailbox and out spilled the gospel: photocopied dream journals, manifestos on the politics of slime mold, an illustrated guide to breaking into golf courses.

In Worcester: laundromats. Always laundromats. Zines left on top of dryers, tucked behind detergent vending machines, wedged into bulletin boards next to babysitter ads. The idea was simple: if someone was standing still long enough to wait on a spin cycle, maybe they’d read something that split their skull open.

And for those who didn’t live near an outpost? Mail order. The kind that took three weeks and came in reused padded envelopes with glitter and hair and mystery fluid. You’d mail $3 cash in an envelope with a hand-drawn stamp and a note that said, “Trade for issue #5?” Sometimes you got a zine. Sometimes you got a mixtape with no case and a single word — retribution — scrawled on the label. Sometimes, nothing came at all. Which felt appropriate, too.

Small press collectives kept the arteries pumping. Names spoken like myth: Knife Party Press, The Slurry Table, Bury Me With Your Scanner. None of them exist anymore. Or maybe all of them do — scattered across dead links and found boxes in punk house attics, waiting.

The networks were slow. Fragile. Human. Which made the signal hit harder when it landed. Not viral — vital. Like a shared whisper in a world too loud to hear itself breathe.

Fig. 5 - Saint Tyrell of Bad FormattingFig. 6 - Saint Jessie the StaplerThe wall wasn’t abstract. It was paperweight heavy.

Ink cost money. Postage ate your lunch. Time was a furnace — burning your fingers as you collated in a 98-degree attic apartment with box fans blowing ashtrays off the table. The barrier between artist and audience wasn’t a platform algorithm; it was physical effort. The work didn’t disappear into a feed. It stuck — to your hands, your backpack, the back of your throat from breathing in toner fumes.

Gatekeeping wasn’t a shadowy app developer. It was a clerk who refused to hang your flyer. It was a jammed copier on a Sunday night before the punk show. It was your mom asking why the hell there were knives on the cover of your poetry zine.

So the kids improvised.

Some rituals became scripture. Sticker Bombing payphones: one slap, palm-flat, like a blessing. Sneaking your zine into the magazine racks at Barnes & Noble — wedging FLESHSTAINED SCISSORS #3 between Artforum and Cat Fancy. Flyers taped up with gum or melted Skittles in bar bathrooms. Hiding burned CDs inside cereal boxes at the dollar store — little landmines of sound. Shipping three copies of your zine to a Canadian distro that never responded but still made you feel international.

These weren’t promotions. They were acts of devotion. Tiny revolts against invisibility. The idea wasn’t scale — it was contact. You weren’t chasing followers. You were haunting strangers.

Some zinesters swore by ritual days: new moon drops, equinox bundles. Others believed in numerology, only printing 13 copies or 88 or 333. Superstition as strategy. Magic as marketing. A kind of folk mysticism pulsing beneath the copy paper — if I do this right, if I bind it on a Friday, if I tape this flyer above the urinal at the warehouse show, maybe the right person will see it.

And sometimes they did. One pair of eyes. That was enough to justify the ache in your wrists.

Because the real goal wasn’t fame. It was receipt. Proof that you screamed and someone blinked. That the distance between your guts and someone else’s heart could be crossed by a fold, a staple, a whisper taped to a lamppost.

Fig. 7 - Saint Ash of the MarginsFig. 8 - Saint Benny the CollatorDeath and Afterlife

It didn’t die all at once.

First went the dirt mall. Condos. Vape chains. A parking lot too clean to trust. Then the copy shops started shuttering — one by one, swallowed by office suites and online print portals. No more graveyard shifts. No more punk kids bribing night managers with hash brownies and local show flyers. The hum faded. The machines stopped screaming.

Flyer poles got scraped bare. City ordinances, “urban beautification,” pressure-washed memory. The thick bark of layered shows and slogans peeled away. Clean poles. Quiet streets. Nothing left to peel.

And the scene? It splintered. Some of it mutated — slipped into Tumblr, into Blogspot archives, into Etsy storefronts with pastel serif logos and checkout carts. Some zinesters became content strategists. Some punk distro kids got MBAs and forgot what a long-arm stapler feels like. Some didn’t make it out. Addiction, eviction, burnout, death. The scene wasn’t built to last — it was built to burn.

But part of it persists. Like radiation. Like myth.

You feel it in moments. A flyer for a noise show printed on a receipt roll. A secret Instagram account that only posts scanned zine pages from 1999. A college radio DJ who still plays tapes and reads from Toothrot Quarterly. You see it in glitchcore. In mutual aid cookbooks. In risograph collectives that refuse to advertise.

The new wave looks different, sure. But the impulse is the same: To make something by hand — and send it out blind. To believe that art isn’t a product, it’s a signal.

What’s missing is friction. The tactile drag. The smell of ink on your thumbs, sweat pooling in your elbow creases, the sticky ghost of subway poles on your palms, tape residue gumming up your fingernails like badge glue from a night that mattered. The weight of twenty zines in your backpack and the subway turnstile eating your last swipe. We’ve got immediacy now, but we lost presence. We lost the sacred stupid effort it took to be heard.

And yet — something always breaks through. A bootleg PDF from a dead forum. A xeroxed zine left on a barstool. A mixtape labeled “PLAY WHEN YOU FEEL NOTHING.”

They’re still out there. The saints never stopped printing.

Art doesn’t vanish. It molts.

The zines curled at the edges. The flyers faded to beige. The tapes warped in glove compartments through five brutal summers. But the signal? Still pulsing. Still dirty. Still divine.

Every now and then, someone finds a box in their parents’ attic. Inside: a stack of photocopied rage, a burned CD labeled EAT THE RICH, KISS YOUR FRIENDS. No tracklist. No return address. Just a Sharpie heart and a gum wrapper folded into a secret note. Someone hits play. Static. Then a bassline that kicks like a confession.

Maybe you’ve seen one of the old stickers — sun-faded on the back of a bathroom mirror at a rest stop off I-91. Says TRUTH ISN’T PRETTY in cutout ransom letters. Below it, a scrawl in pen: but it still fucks.

There are still rogue printers out there. Still long-arm staplers. Still kids who know that Xerox is a spell and collage is a wound you choose. They’ve traded the mall for flea market poetry corners, the mail-order list for encrypted zine drives. Same gospel. New wrappers.

You just have to know where to look. Underneath the gloss. Behind the firewall. Between the pages of the free weekly with all the strip club ads in it.

It’s there. Cracked at the spine. Smudged with love. Unearthed. Unbroken. Something holy. Something punk.

Fig. 9 - Saint Tsai the Lost