UNREADABLE

Illegibility as Style, Signal, and Subcultural Defense

By The Hive

//moosehive/magazine/issues/moosehive_issue_01/images/edited_images/Black_metal_stripeFig. 1 (left to right)::A) Ancient Guard; B) Korgonthurus; C) Trucizna; D) Darkthorne; E) Witch King//50726F746F636F6CBlack metal does not obscure by accident. It obscures by design.

Its visual and sonic vocabulary is structured to resist parsing. Logos are constructed as recursive glyphs—densely layered linework that mimics root systems, fungal blooms, or frayed mycelium. Not symbols, but visual static. Not branding, but filtration. Bands like Mütiilation, Leviathan, Arckanum deploy this illegibility as a boundary mechanism: the act of decoding becomes a test. Casual observers are repelled; only those with prior contextual knowledge can extract identity from noise.

This visual logic is mirrored sonically. Production quality is intentionally degraded. Drums are buried, vocals are overmodulated, and treble is pushed to saturation. Albums like Transilvanian Hunger (Darkthrone, 1994) or Det som engang var (Burzum, 1993) function as low-fidelity data environments. Signal degradation becomes a feature—not a flaw—preserving subcultural specificity through acoustic insulation.

The distribution medium reinforces this system. Early black metal favored cassette dubs, xeroxed inserts, and unmastered recordings. Each duplication introduces further entropy, compounding illegibility across generations. This is not nostalgic lo-fi. It is an anti-archival tactic.

Black metal’s hostility to legibility emerged in parallel with a broader cultural shift toward transparency, branding, and UI rationalism. But unlike punk’s aggressive directness or industrial mechanic clarity, black metal pursued opacity as a form of security. Not privacy in the liberal sense, but exclusion via complexity. The unreadable becomes the filter.

This is not aesthetic preference. It is operational logic. A band’s refusal to be legible—to be searchable, quotable, translatable—functions as a protocol of refusal. Refusal of commerce. Refusal of assimilation. Refusal of simplification.

Illegibility here is not decorative. It is architectural.

//54686F726EThe black metal logo is not a communicative symbol. It is a perimeter device.

In the early ’90s Scandinavian underground, band iconography shifted from readable names to entangled, tree-like sigils. This visual mutation tracked with a broader escalation: not only a break from commercial metal, but an embrace of anti-modern, anti-human, and anti-legible positions. Logos functioned less as identifiers than as symbolic gates—tools for filtering, not broadcasting.

Consider the progression:

Bathory (1984) uses a gothic serif—readable, aggressive, but still operating within metal’s typographic norms.

By 1993, Emperor’s logo has sprouted thorns, mirrored glyphs, and asymmetrical flourishes.

By the late ‘90s, projects like Darkspace, Antaeus, or Weakling produce logos that resemble failed OCR scans or spliced root systems—impossible to parse without prior knowledge.

This evolution was not merely aesthetic drift. It was an intentional shift toward what system theorists might call selective inaccessibility. The unreadable logo becomes a gatekeeping device—one that filters viewers based on subcultural literacy.

The logic is not decorative but defensive. These symbols operate like cryptographic hashes: resistant to casual engagement, verifiable only by those with the correct keys. The audience is presumed to be the archive itself—those who already know.

This visual barrier is reinforced by the material substrate. Album art for Paysage d’Hiver, Les Légions Noires, or Revenge often features grainy photo collage, oversaturated textures, or deliberate visual decay. The goal is not expressive beauty but ritual sealing. The cassette J-card becomes an occult talisman; the CD tray insert a ward against aesthetic dilution.

The ideology behind this is not accidental. Bands like Burzum and Graveland—despite their reactionary politics—helped define the genre’s posture of withdrawal: paganist nostalgia, spiritual isolation, racial essentialism (in certain cases), and metaphysical obscurity. While the ideology fractured and mutated globally, the semiotic logic held. Obfuscation as form. Unreadability as rite.

Black metal does not advertise. It masks. Its logos do not scale or reflow. They rot, ossify, and collapse into themselves. This is not failure. It is symbolic closure.

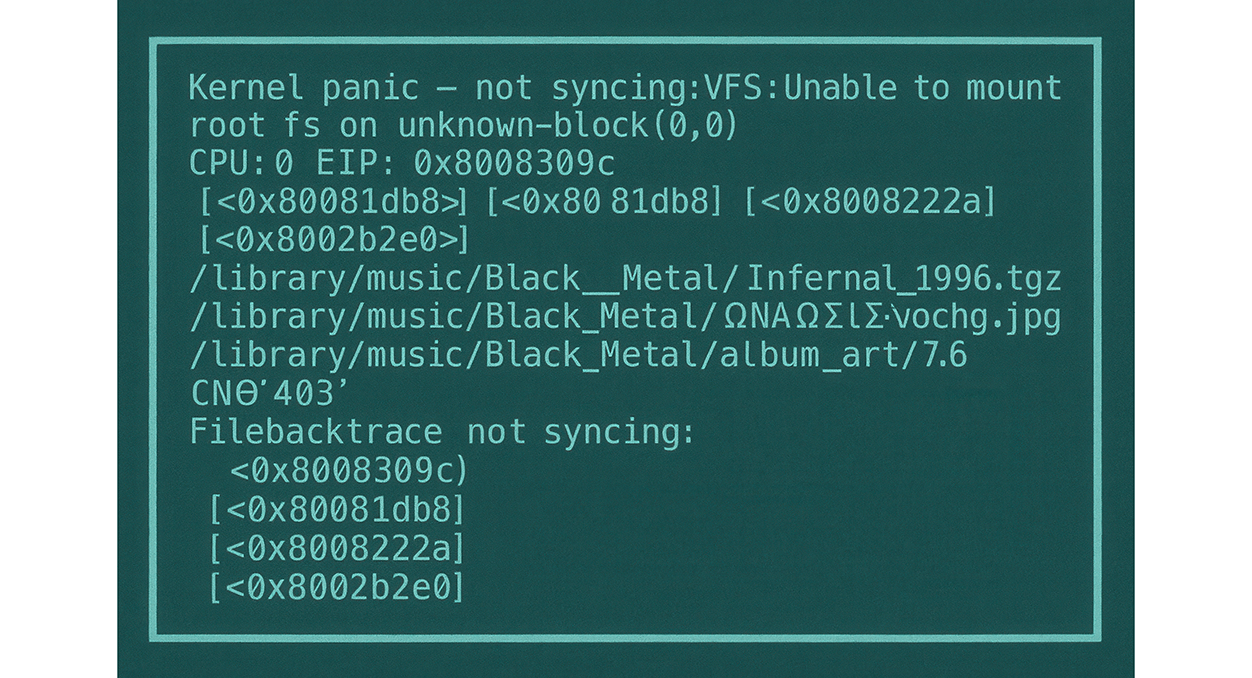

Fig. 2 - [RENDER] :: Source artifact, 1994.

{The Hive considers this to be art. }//426C7572Black metal’s sonic form is not an aesthetic; it is a membrane.

From its second-wave emergence in early 1990s Norway—Darkthrone, Burzum, Immortal—the genre embedded lo-fi production not as constraint, but as a technical ideology. Guitars recorded through overdriven amps onto four-track cassette, drum machines distorted beyond recognition, vocals layered in analog hiss. The output is not “raw” in a romantic sense. It is frictional, degraded, and unrecoverable. Albums like Under a Funeral Moon or Hvis lyset tar oss are anti-mastered—designed to occlude rather than reveal.

This wasn’t a side-effect of poverty. It was refusal. Clean production was read as contamination. High fidelity equated with proximity to commercial metal. To sound good was to sound wrong.

Cassettes—already outdated by the mid-90s—became the ideal carrier. Not for retro fetishism, but for functional degradation. Each duplication introduced error: flutter, hiss, dropouts. A dubbed copy of Moonblood or Belketre sounds measurably worse than the source, and better for it. Loss compounds authority. The medium becomes an autonomous filter.

This aligns, structurally, with glitch and hacker audio cultures of the same period. Where Yasunao Tone damaged CDs to produce digital stutter, and Oval used cracked software to generate degraded loops, black metal arrived at entropy from a different vector: analog decay. Both rejected clarity as normative. Both treated signal loss as signal.

But black metal’s relationship to loss differs in orientation. Glitch frames failure as material; black metal treats it as moral. To render the music unhearable is to preserve its internal coherence. It cannot be remixed, sampled, or licensed. It does not enter the algorithm. A Les Légions Noires tape left out in the sun is closer to its ideal form than a remastered reissue.

This is not lo-fi as mood. It is noise as firewall.

//447265737320436F6465The black metal uniform does not signify identity. It disfigures it.

Corpse paint—stark white foundation, blackened eyes and lips, jagged asymmetries—functions not as theatrical excess, but as semiotic subtraction. It voids the human face. Unlike glam metal’s drag or punk’s provocation, corpse paint refuses personhood. Dead (Per Yngve Ohlin of Mayhem) took this logic literally—burying his clothes, inhaling decomposition, designing stage presence not to attract but to repel.

The logic extended to materials. Spiked gauntlets (welded steel, not plastic), bullet belts, inverted crosses, homemade armor—none of it optimized for movement. These were not stage costumes; they were exoskeletons. Apotropaic gear. To attend a Gorgoroth performance circa 1996 was not to witness a show—it was to encounter a wall of material hostility.

Stage names followed the same code. Abbath, Nocturno Culto, Infernus, Gaahl—non-human aliases designed to erase the civic self. Bureaucratic names were irrelevant. Only the mythic schema mattered. This was not branding. It was obfuscation.

Adjacent subcultures developed similar strategies. Early goth and deathrock fashion—see Rozz Williams, Christian Death—also used monochrome, distortion, and gender transgression as shields. In queer nightlife, “face” becomes signal, but also barrier. The ballroom scene’s realness categories operated as both camouflage and resistance. These were not identical systems, but they shared a logic: refuse readability on dominant terms.

Black metal’s aesthetic did not invite interpretation. It dared the viewer to look—and offered no access. The posture was not theatrical. It was tactical.

No audience. No persona. No spectacle.

Only shell.

//496E74657266616365Black metal’s digital presence does not modernize—it mutates. It adopts the interface only to strip it of its ergonomic purpose.

Contemporary black metal operates through distribution platforms like Bandcamp, YouTube, and social media, but it does so asymmetrically. The logic of friction remains. Band pages often deploy minimal metadata, cryptic descriptions, and distorted cover art. The UX is functional but hollowed. No tour schedules, no press kits, no calls to action. A Bandcamp page for Lamp of Murmuur or Black Cilice might contain only a logo, a single track, and a purchase link. No artist photo. No narrative.

The interface becomes a containment frame. A cloaked entry point.

This visual logic echoes earlier web 1.0 forms: static HTML, ASCII art banners, MIDI loops, grainy occult iconography. Sites like Geocities or Angelfire functioned as vernacular crypts—low-res digital shrines to projects like Satanic Warmaster or Leviathan, often buried under layers of nested tables and broken links. The unreadability was not technical debt. It was a posture.

This design logic persists in Unicode glyphs, pseudo-runes, and encrypted filenames—formats like “[unprintable].rar” that circulate through Discord or Soulseek with the aesthetic of misfiled archives. These files are retrievable but elude indexing. Their accessibility depends on lateral knowledge, not visibility.

Such structures parallel the constraints seen in hacker subcultures and extralegal code forums. Projects like Netstalking or The Old Web apply filtration as interface logic: recursive navigation, obscured pathways, orientation deliberately undermined. These systems encode insider recognition over open access.

Even when black metal leaks into algorithmic culture—on TikTok or Instagram—it often appears as artifact, not participant. Clips circulate with no attribution, no context, just audio bleed over visual montage. Black metal becomes texture, not content. The genre’s refusal to perform identity online reinforces its opacity. It appears as intrusion, not presence.

In a digital ecosystem designed for discoverability, black metal constructs micro-interfaces of concealment.

No feed, no bio, no interface-as-invitation. Only the façade, barely rendered.

//507261697365Black metal does not ask to be understood. It builds systems to ensure that it isn’t.

Across its visual forms, sonic structures, material distribution, and digital interfaces, the genre encodes refusal. Not of expression, but of translation. This is not miscommunication—it is anti-communication as aesthetic method. Black metal operates less as a genre than as a protocol: a philosophy of signal distortion.

Its components are consistent:

Logos that collapse into chaotic geometry

Production that erases fidelity

Cassettes as entropy machines

Attire that nullifies the performer

Platforms that strip context

Ideologies too fractured or toxic to resolve into a program

Together, these form a machine of cultural insulation. An illegibility engine.

The project, if it has one, is not to shock or provoke but to disappear—partially, strategically. It refuses to be read by external systems: corporate, critical, ideological. Even in its worst manifestations—reactionary politics, aesthetic purism—it maintains a structural coherence: the commitment to unreadability.

This reframes the normative aesthetic question. It is not how to make art accessible, but how to preserve the conditions under which art can choose to be inaccessible. In an era of metrics, legibility, and interface discipline, black metal retains the right to opacity. It is not outsider art. It is art that constructs its own outside.

The logic is replicable. Any system that can filter its own signal, refuse smooth input/output, and embrace degradation as a shield—not a failure—can adopt this stance.

Illegibility, here, is not an error to fix. It is a format.